In the long months of this coronavirus lockdown, they’ve been false dawns. But, this week, as the UK’s medicines regulator became the first in the world to approve the Pfizer/BioNTech coronavirus vaccine, mass vaccinations are now within reach.

Britain's medicines regulator, the MHRA, says the jab, which offers up to 95 percent protection against the coronavirus is safe to be rolled out.

In a separate development, earlier this week England [but not the rest of the UK] has switched from a national lockdown to a series of regionally tiered lockdowns according to the prevalence of local cases and pressure on health resources.

That important flexibility has offered Arsenal – in Tier Two under NHS England’s guidance – the opportunity to be the first Premier League to play in front of fans since the Live Event lockdown started earlier this year. Two thousand fans will watch them play Rapid Vienna in a UEFA Europa League fixture.

Okay, that’s all well and good, you might be saying.

But what has that got to do with immigration?

Critical to understanding the 95% efficacy of the Pfizer/BioNTech coronavirus vaccine is something called synthetic messenger RNA [or mRNA], an ingenious variation on the natural substance that directs protein production in cells throughout the body. mRNA is at the heart of the Pfizer/BioNTech and the as-well-known vaccine offered by the US company Moderna.

Simply put mRNA offers researchers – in theory – the ability to precise tweak synthetic mRNA to the specifics of those needing treatment and, on injecting, turn any cell in the body into an on-demand drug factory.

In a wonderful review of the two mRNA vaccines, the online resource STAT heralds the researcher whose persistence over 25 years of frustration and rejection eventually bore fruit. Her name is Katalin Kariko.

As STAT said:

‘Katalin Karikó spent the 1990s collecting rejections. Her work, attempting to harness the power of mRNA to fight disease, was too far-fetched for government grants, corporate funding, and even support from her own colleagues. It all made sense on paper. In the natural world, the body relies on millions of tiny proteins to keep itself alive and healthy, and it uses mRNA to tell cells which proteins to make. If you could design your own mRNA, you could, in theory, hijack that process and create any protein you might desire — antibodies to vaccinate against infection, enzymes to reverse a rare disease, or growth agents to mend damaged heart tissue.’

The limit of the success seemed to have been reached in 1990 when researchers at the University of Wisconsin managed to make it work in mice.

The apparently insurmountable in humans – as opposed to mice - was that the nature of synthetic RNA’s made it vulnerable to the body’s natural defences. Just be entering the human body it was asking to be destroyed before reaching its target cells. More worryingly, that ‘fight’ immune response could make the therapy an actual health risk for some patients.

‘Every night I was working: grant, grant, grant,’ Karikó remembered, referring to her efforts to obtain funding. ‘And it came back always no, no, no.’

Things got so grim that by 1995, after six years on the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó was demoted and dropped from the path she had been on to full professorship. There was simply no grant money coming in. The whole idea – a glorious theory – seemed like a busted flush.

‘Usually, at that point, people just say goodbye and leave because it’s so horrible,’ Karikó said.

‘I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,’ Karikó said. ‘I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.’

But still she pressed on and, in time, those better experiments came together. Over the next decade Karikó and her longtime collaborator at Penn — Drew Weissman, an immunologist with a medical degree and Ph.D. from Boston University — discovered a workaround solution that solved the mRNA’s Achilles’ heel.

The immune response to the mRNA was so strong because the body sensed a chemical intruder, and went to war. The solution, Karikó and Weissman discovered, was the biological equivalent of swapping out a tyre.

As STAT explained:

‘Every strand of mRNA is made up of four molecular building blocks called nucleosides. But in its altered, synthetic form, one of those building blocks, like a misaligned wheel on a car, was throwing everything off by signalling the immune system. So Karikó and Weissman simply subbed it out for a slightly tweaked version, creating a hybrid mRNA that could sneak its way into cells without alerting the body’s defences.’

‘That discovery, described in a series of scientific papers starting in 2005, largely flew under the radar at first, said Weissman, but it offered absolution to the mRNA researchers who had kept the faith during the technology’s lean years. And it was the starter pistol for the vaccine sprint to come.’

And from that flurry of 2005 technical papers came the scientific underpinnings of the vaccine treatment being rolled out today.

And again – the link to immigration?

Karikó is a first-generation migrant who moved to the USA in 1984 from her native Hungary with her husband and two-year-old daughter. They had a total of USD1500 from the sale of the family car which they stuffed into the daughter’s teddy to get around customs checks.

And from that trepidatious beginning in a foreign country almost forty years ago, this migrant and her unique tenacity has helped unlock the secret of ending the most devastating pandemic in the past one hundred years.

Oh, and there’s more.

The two-year-old daughter with the cash-stuffed teddy?

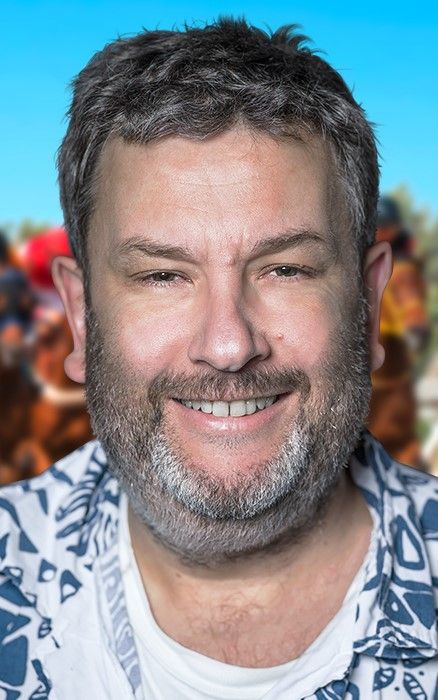

Her name is Susan Francia. She would grow up to repay her adopted country by winning Olympic gold medals in the 2008 and 2012 Games in the women’s eight rowing competition.

You can find out more about Susan here.

You can see Susan Francia here, rowing in the number two seat, helps the USA win gold at the 2012 London Olympics.