You might have got to this first line thinking the article was going to be all about the stewarding arrangements at Wembley for the 2020 UEFA European Championships finals.

That bit will come later.

Bear with me please. One of the things that the UEFA Euros this summer inadvertently achieved was to obscure any real coverage, and therefore public debate, following the publication of the public inquiry into the Manchester Arena Inquiry into the 2017 suicide bombing that claimed 22 lives as music fans left the venue after an Ariane Grande concert.

The report was published on June 17, the day before England’s 0-0 draw with Scotland and the day following Italy’s 3-0 win over Switzerland.

Not surprisingly, considering the suicide attack was on its own patch and the newspaper used to be the title sponsor of the Arena itself, the Manchester Evening News devoted the most coverage to both the day-to-day business of the inquiry and the devastating conclusions reached by chairman Sir John Saunders.

Good morning from the Manchester Arena Inquiry.

— Mat Trewern BBC Manchester (@mattrewern) July 22, 2021

Today we'll hear from 3 survivors of the bombing:

1. Martin Hibbert

2. Claire Booth, whose sister Kelly Brewster died in the attack

3. Bradley Hurley, brother of Megan Hurley who also died in the atrocity@BBCRadioManc @BBCNWT pic.twitter.com/AoNFt90Cy0

In a comprehensive review published on June 20, the MEN took readers through what Saunders considered to be those whose actions had 'fallen below a proper standard in carrying out their important roles in protecting concertgoers'.

As the MEN wrote: ‘Sir John said there were a number of opportunities to identify hate-filled suicide bomber Salman Abedi’s activities as being suspicious on the night, before he detonated his bomb.

‘But [Saunders] went on: "What I cannot say with any certainty is what would have happened if those opportunities had not been missed. Salman Abedi might have been deterred from committing this outrage or might have done the same thing elsewhere.

The inquiry is shown footage of the bomber apparently speaking to a Showsec steward on 'reconnaissance trip'https://t.co/jLt8aaTDpy

— Manchester News MEN (@MENnewsdesk) December 9, 2020

‘"He might have detonated his bomb earlier in a different location, in or close to the City Room.

‘And in what might be considered Sir John's most chilling comment, he said: "Everybody concerned with security at the Arena should have been doing their job in the knowledge that a terrorist attack might occur on that night. They weren’t.

‘"No one believed it could happen to them."’

The MEN’s summary of the Saunders’ report identified specific areas of concern relating to the policing of the event, the Arena operator, CCTV blindspots and the operation of the National Terrorism Threat Level.

But two specific additional criticisms were made that linked the issue of stewarding: the company providing the stewards, Showsec, and the actions of the stewards themselves.

The inquiry heard how a member of the public, Christoper Wild, had raised concerns about the suicide bomber to a Showsec steward - Mohammed Agha.

‘Had Mohammed Agha been more alert to the risk of a terrorist attack, he had a sufficient opportunity to form the view that Abedi was suspicious and required closer attention,’ said the report. ‘This conclusion, had Mohammed Agha been adequately trained, would have caused him to draw Abedi to his supervisor’s attention at this stage.’

Showsec, said the report, 'failed adequately' to train Mr Agha, who, it said, bore a degree of 'personal responsibility for this missed opportunity' too.

The second criticism the report makes directly is that of the stewards themselves – and here we loop all the way back to the UEFA European Championships finals where amongst many other obvious failings, there was also a failing to stand up a proper stewarding plan and some of the stewards themselves went awry.

On the night in question the bomber, Salman Abedi, had been standing around the exits to the stadium for over an hour and a quarter.

As the Spectator columnist Douglas Murray wrote in a column sympathetic to minimum-wage stewards entitled ‘Why We Don’t Always Say What We See’:

‘You would have thought that the sweaty young man with a rucksack might have attracted some attention. And you would be right. A number of people, including security guards hired to protect the venue, expressed alarm about the man struggling to walk because of the weight of his rucksack, which was packed with a 32kg bomb. One, called Kyle Lawler, had the honesty to tell the inquiry about his reaction. He said that he sensed that there was “something wrong” about Abedi. He said that Abedi had “a slightly nervous reaction” when people looked at him and that he “seemed fidgety”. Lawler admitted that he wasn’t sure what to do and that although the national terror threat level was at Severe, he knew nothing of any “potential attack”.

‘The report goes on: “He [Lawler] stated he was fearful of being branded a racist and would be in trouble if he got it wrong.”’

One might imagine the right-leaning politics of the Spectator would not make them natural allies of minimum-wage stewards, but Murray’s conclusion about the actions of Lawler was thunderous:

‘As Jonathan Hall QC, the government’s Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, said: “The Manchester Arena attack wasn’t about a failure to combine information. It was a failure to see what was actually there.” Sometimes, he went on, “stopping terrorism is about seeing what is there in front of you”.

‘Yet who would do that? When asked what Mr Lawler ought to have done, Jonathan Hall’s only answer was that people should have more confidence. Which is easy to say. [Lawler] wasn’t some powerful police supremo. He only worked for one of those crappy security companies who give a veneer of security at public events before things really get serious.’

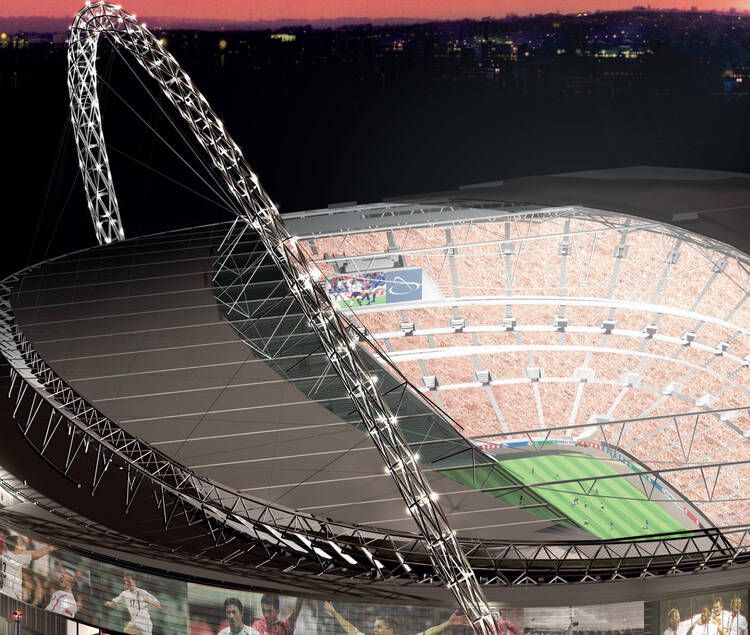

And so to the UEFA European Championships which was meant to be this summer’s biggest-ever sporting event: England winning their first major trophy since 1966, a dazzling showcase for an ambitious British and Irish plan to co-host the FIFA World Cup in 2030 and the throwing off – at last – of almost eighteen months of on-again, off-again lockdowns across Europe amidst general dread and pessimism.

Instead, the finals of the 2020 UEFA European Championships turned into a fiasco, a drunken orgy of violence from red-faced screaming fans who overwhelmed the ticketing, stewarding and entry protocols. The common consensus amongst those of us who attended or had clients at the match was that we were all lucky there were no deaths.

It says something that the first person convicted was a teenager, working as a steward at Wembley Stadium.

Idiots at Wembley for the riot police to deal with #Euro2020Final #ENGITA pic.twitter.com/Iw5Fv7Vcv7

— Dan Dicker (@dandicker83) July 11, 2021

Eighteen-year-old Yusaf Amin from Canning Town in London, stole official lanyards, hi-vis jackets and wristbands and offered to sell them online for a total of £4,500.

The youngster, who pled guilty, was handed a six-month sentence in a young offenders’ institute, suspended for a year.

He was also asked to pay £213 in legal costs, carry out 200 hours of unpaid work and go to an attendance centre.

Separate investigations have been opened by UEFA on issues surrounding the final and an independent one commissioned by the Football Association.

A second eighteen-year-old, part-time Wembley steward Dalha Mohamad from Waltham Forest, was charged with similar offences at the same time as Amin. He has plead not guilty and is due to go on trial on December 17 this year.

The court was told that Amin had made a post to Facebook’s Marketplace at 3pm on match day which read: ‘Steward pass available x2 with uniforms and pass and I’m outside Wembley, anyone wans (sic) to get in.

‘I have two passes and two uniforms and wristbands for you to go in and watch the game.

‘Looking for serious people only. Guaranteed entry or money back.’

The handover was due to be made at a local Aldi supermarket.

Immediately following the match, the football correspondent of The Times Henry Winter listed a series of questions to the Football Association, after aggressive cost-cutting in 2015, that he felt needed answering.

These included:

- Did you, the Football Association, get rid of old and trusted systems and processes that were in place?

- You planned for this event, so where in your checks and balances did it go wrong?

- Is there a culture at the FA where staff can question management and raise concerns?

- Are the staff who manage the external areas of Wembley trained by the Metropolitan Police in responding to public order incidents, as they were in the past?

- Who decides when crowd management, which is the FA’s job, becomes crowd control, the Met’s responsibility?

- What were the thoughts of the experienced safety officer and the silver commander who were overseeing the event?

- Was there a reduction in security checks on fans? Was the watchlist of known “problem” fans properly scrutinised?

- Is sufficient training given to the upwards of 1,000 people you employ for crowd control on event day? Could you do more training of more supervisors responsible for those stewards? Are the stewarding companies accountable enough?

- There used to be bigger teams around the turnstiles, including an emergency response team and Security Industry Authority-qualified stewards, sometimes with police outside turnstile blocks to protect them. Has cost-cutting affected this?

And then perhaps one question that really goes to the heart of the issue: ‘Would you fight coked-up, ticketless fans for £11 an hour?’

Maybe it’s time also to look at ourselves and wonder whether the whole Live Event Industry has become too addicted to the tick-box exercise that is minimum-wage stewarding.